Human Rights Compass serves as a platform for real-time human rights policy analysis and strategic coordination through:

» Convening key human rights stakeholders for coordinated policy advice and action.

» Publishing policy briefs and analysis about the Top Human Rights Trends to inform and guide advocacy.

» Promoting principled responses to systemic challenges that undermine international human rights frameworks.

Our convenings brought together over 120 human rights defenders, policy analysts and multilateral actors to examine how the ongoing changes affect international justice, foreign aid and human rights protection, and to promote appropriate solutions.

Human Rights Compass is powered by Progress & Change Partnerships and Palimpsest GmbH.

Defending Rights in Turbulent Times

Human Rights Compass is about real-time policy analysis and action. It aims to strengthen human rights as a framework.

Human Rights Compass Policy Papers

GLOBAL REALIGNMENT

SAVING LIVES,UPHOLDING RIGHTS

DEFENDING DEFENDERS

HUMAN RIGHTS AT STAKE

10 Top Global

Human Rights Trends

Human Rights Compass is publishing its Top 10 Human Rights Trends ahead of the 61st session of the United Nations Human Rights Council.

They are grounded in a simple assessment: we are living through a global realignment in which overlapping crises have hardened into a fractured order.

Wars are prolonged rather than resolved. Repression is normalised. And human rights are too often treated as optional commitments, applied when convenient and ignored when costly.

Civilian harm is rising as legal restraints are weakened or ignored, and accountability is obstructed or attacked. Securitisation is back as a governing instinct, with states framing security and human rights as a trade-off and expanding emergency powers, surveillance, and restrictions on dissent. Multilateral mechanisms remain essential for victims, but political follow up is often missing, while coalitions of the willing can reinforce selective cooperation and leave affected communities out.

The trends we identify show how this shift plays out across regions and institutions.

This pressure is also reshaping democracy and civic life. Civic space is moving from shrinking to a war on NGOs, where funding controls, foreign agent laws, protest bans, digital shutdowns, and violence against civil society actors combine into a model of power consolidation.

At the same time, human rights defenders are being delegitimised, criminalised, and targeted across borders, including in exile. Defending human rights defenders is no longer a specialised concern. It is a test of whether societies still accept independent civic engagement as a public good.

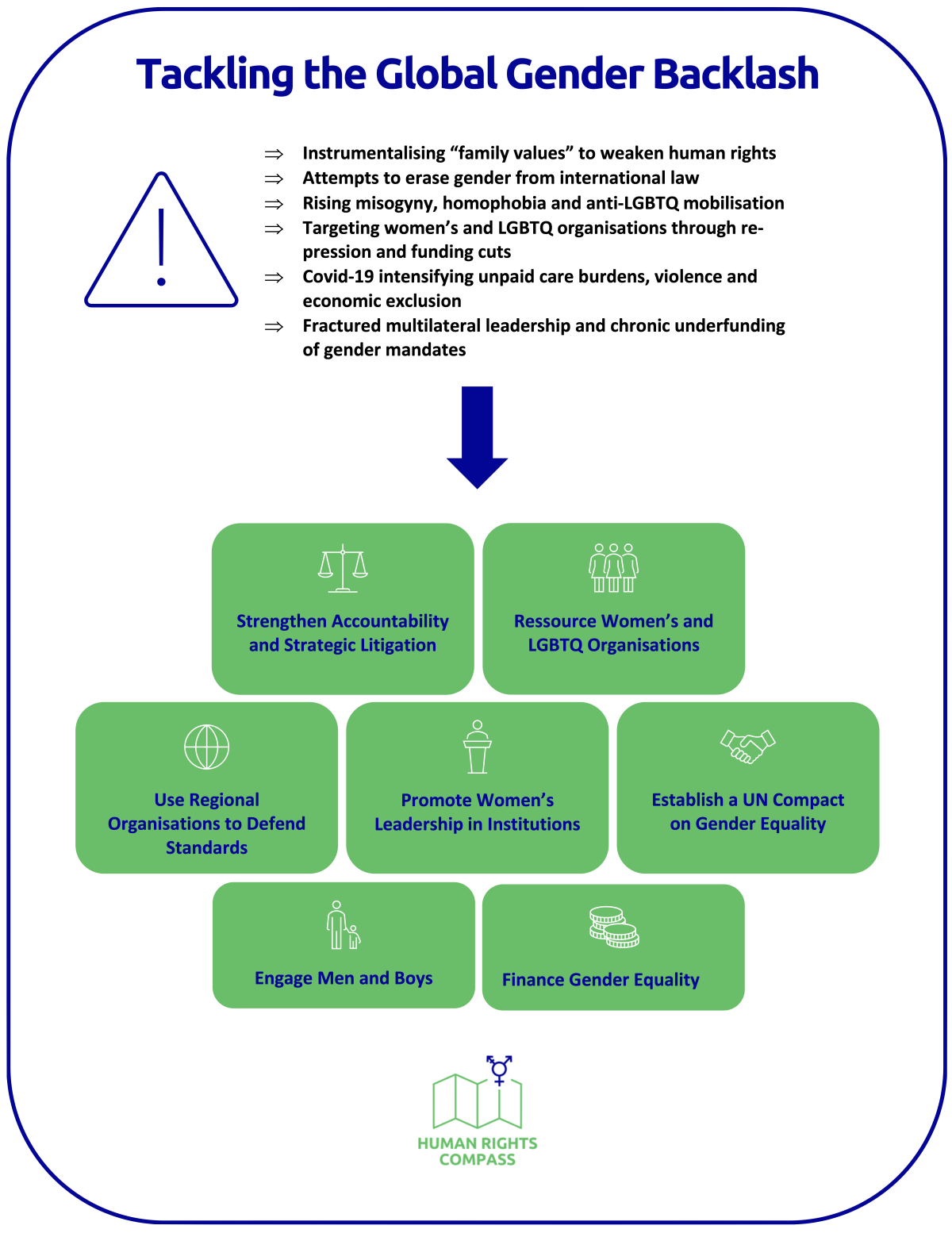

The Top 10 Human Rights Trends also tracks the gender backlash as a central battleground in this moment. Women’s rights and LGBTQ rights are rolled back through law, policy, and coordinated narratives that use gender as a political weapon. This backlash is networked, funded, and strategic. It is also linked to wider attacks on institutions, information integrity, and civic space. When gender equality is framed as negotiable, the wider idea of universality is weakened.

Across all ten trends, the thread is the same: without protection, accountability, and civic participation, insecurity deepens rather than recedes.

1. Protracted Wars, Civilian Harm, and the Erosion of Accountability for Atrocity Crimes▾

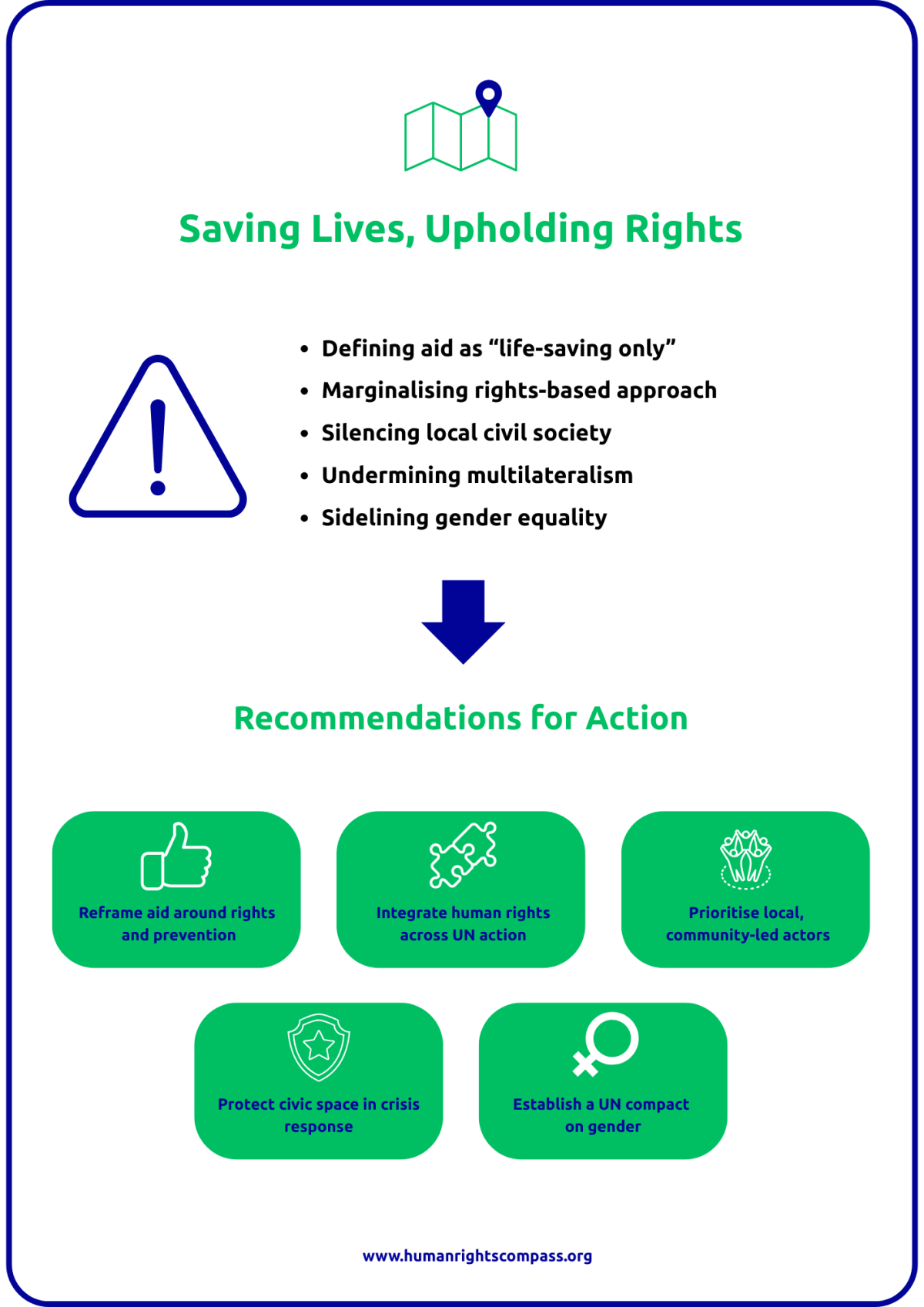

Protracted wars are becoming the new normal, with civilians increasingly being targeted. Legal restraints are weakened or ignored, and attacks on civilian infrastructure are normalised. Accountability mechanisms are obstructed, delayed or undermined, including through intimidation of international justice actors. Humanitarian responses are being forced to narrow to “life-saving” action, leaving violations and structural risk factors and root causes of atrocity crises unaddressed and reinforcing impunity.

To counter this trend, accountability must be placed at the heart of civilian protection. States and institutions should reject political deals that trade peace for impunity, defend the independence of international justice, and protect investigators, judges, and prosecutors from retaliation. Humanitarian actors and donors should also establish stronger links between emergency action and human rights protection, including preserving evidence and supporting victims’ access to justice. Accountability must go beyond criminal proceedings and include a full range of forms of political accountability.

At the same time, civilian protection must be embedded in diplomacy and security policy, including stronger controls on arms transfers and monitoring of compliance with international humanitarian law. Local documentation and survivor-led accountability efforts require sustained protection and funding, including for groups active in exile. The message must be consistent: violations do not become acceptable because a war has been ongoing for a long time.

2. The Return of Securitisation and Marginalisation of Human Rights ▾

Once again, states are suggesting that we must choose between human rights and security, across areas like migration, protest, public health, climate action, information, and civil society financing. This false dichotomy allows for a simplified introduction of emergency powers, expanded surveillance, and restrictions on dissent, and often frames rights as an impediment to other state interests rather than an integral part of them Over time, states treat rights as conditional commitments that can be withdrawn when they become inconvenient rather than universal obligations. This weakens the rule of law, with marginalised groups and defenders bearing the brunt of the impact.

To counter this trend, we must reject the idea that societies choose between security and rights. Security frameworks must include civil liberties safeguards, parliamentary scrutiny, and judicial oversight from the start, not as an afterthought, reviving the idea of “human security.” Policies should be reframed around this broader conception of security, including social protection, civic participation, independent media, and trust in institutions.

Human rights defenders should be recognised as partners in prevention and resilience, rather than being viewed as risks to be managed. Oversight bodies and courts need resourcing and political support to stop emergency measures from becoming permanent. The Women, Peace and Security agenda must remain central to security thinking, because gender-blind securitisation deepens exclusion and instability.

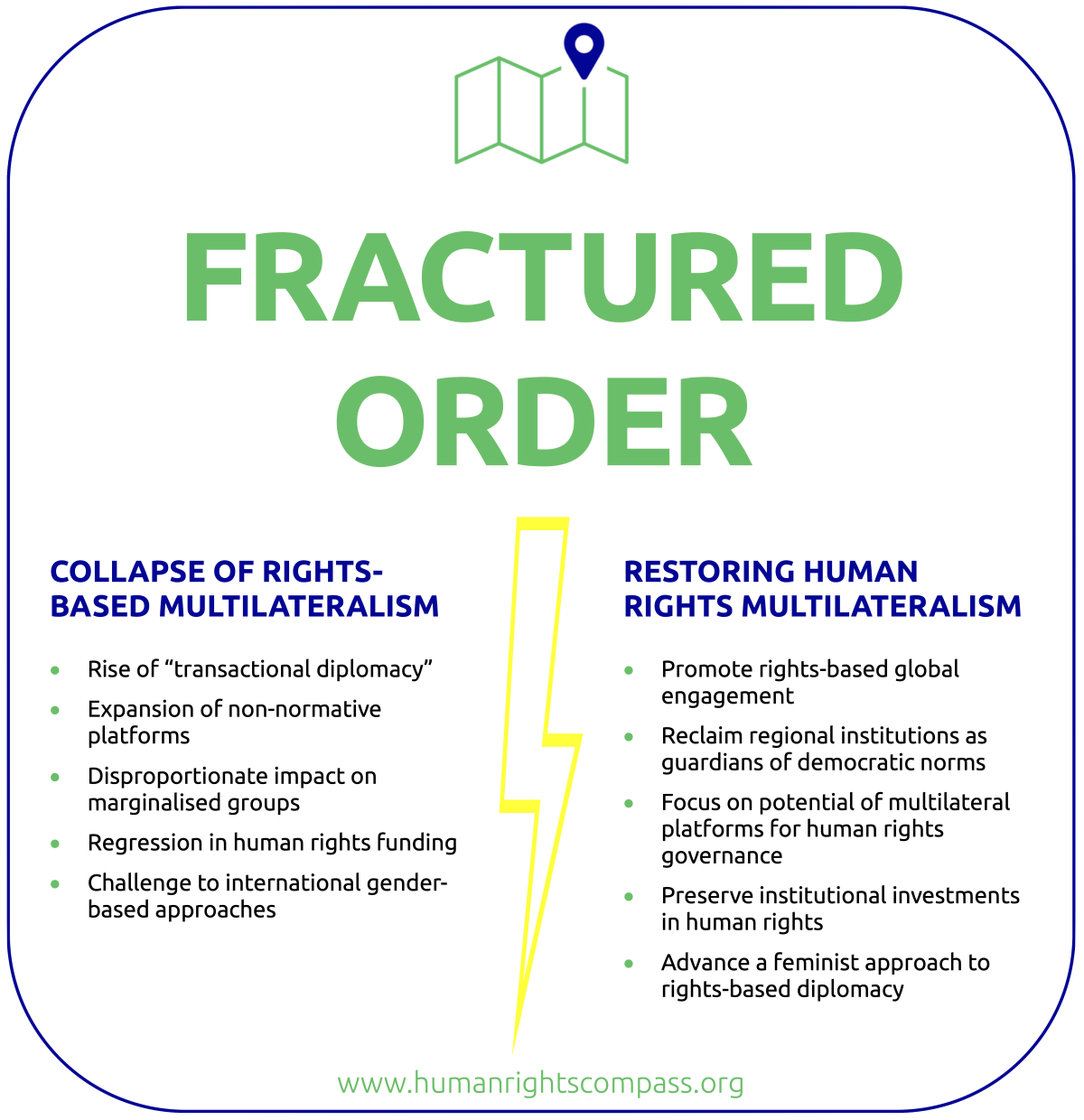

3. The Crisis of Multilateral Legitimacy and the Turn to Coalitions of the Willing ▾

Multilateral institutions are widely perceived as slow and politicised, and as being unable to protect people in times of crisis. Though they often remain the only place for victims to go, it is the absence of political follow up that limits their effectiveness. States withdraw, defund, and undermine these institutions, which also fail to follow through on clear warning signs. In response, coalitions of the willing are promoted as a pragmatic alternative, but they often lack accountability and exclude affected communities. This normalises selective cooperation and makes protection contingent on geopolitics rather than law. Building such coalitions outside of the UN context also requires establishing contacts with numerous governments beyond Europe and North America as well as an in-depth understanding of their positions on various human rights issues.

To counter this trend, we must reject the false dichotomy of paralysed multilateralism and unaccountable coalitions. Multilateral bodies require more robust political follow-up and follow-through mechanisms, alongside systematic engagement with local civil society and clearer political consequences for ignoring warnings. Human rights mechanisms also require predictable funding and collective political defence when attacked or intimidated.

Coalitions of the willing, where they exist, should be transparent, bound by international human rights law and accountable to multilateral oversight. Regional systems should be reinforced as practical pillars of protection and accountability. States that claim to support multilateralism must show it in practice, even when it incurs political costs, and should collaborate with civil society groups across countries.

4. The Erosion of Human Rights Leadership and Political Lethargy ▾

Although Europe’s human rights commitments remain strong on paper, political will is weakening and leadership is hesitant at the level of European states, the Council of Europe, and the European Union. Attacks on the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and the Convention system are growing and human rights are treated as negotiable in the face of security, migration, and far-right electoral pressure. This undermines public trust in and understanding for those institutions and creates space for authoritarian influence.

Europe must treat human rights as a strategic interest linked to democratic resilience and long-term security. This requires defending its own legal architecture unequivocally, including the Council of Europe, the authority of the European Court of Human Rights and full implementation of its judgments. Migration and security policies should be shaped by human rights-based approaches, not by copying exclusionary narratives that legitimise far-right framing.

Europe also needs to rebuild public trust, with civil society as a partner and an early warning system. Consistency is paramount in external relations; double standards corrode influence and undermine the case for international law. Leadership is restored through choices that show human rights are not optional when the pressure rises.

5. The Normalisation of Far-Right Populism and Its Appropriation of Protection and Welfare Narratives ▾

Far-right populism is moving from the margins into government, administration and mainstream debate. It redefines “protection” and “welfare” to justify exclusion, harsh policing, and conditional access to rights. It also fuels identity-based grievances, including framing of racism as “defending” those who are perceived as being treated unfairly, as well as a politics of masculinity that targets gender equality and LGBTQ rights. Antisemitism is being manipulated in complex ways; some actors are claiming to combat it, yet are enabling antisemitic narratives and alliances.

To counter this trend, social protection and solidarity should be reclaimed as a human rights project, based on universal social security, robust public services, equitable taxation, and dignified working conditions. Democratic institutions should treat the normalisation of the far right as a governance risk and strengthen safeguards against discrimination, protecting the courts, regulators, and the integrity of elections and media spaces.

Responses to antisemitism must be consistent and credible integrated into wider efforts to combat racism, discrimination and xenophobia, and far-right actors must not be allowed to exploit the fight against antisemitism to advance racist and conspiratorial politics. Civil society also needs a stronger local presence and to forge alliances with groups beyond traditional human rights circles, such as unions, community and faith groups and professional associations. This is how exclusionary narratives lose their grip on everyday life.

6. The Global Gender Backlash and the Rollback of Women’s and LGBTQ Rights ▾

Women’s rights and LGBTQ rights are being rolled back through law, policy, and coordinated public narratives that portray equality as a threat. Gender and sexuality are used as political tools to polarise societies and justify institutional capture and executive overreach. Far-right actors often use “protection” rhetoric to target education, bodily autonomy, and LGBTQ visibility, while presenting themselves as defenders of social order. The result is that discrimination and violence become easier to deny, and the idea that some rights are optional gains ground.

To counter this trend, gender equality and LGBTQ rights must be treated as core democratic infrastructure. Rolling out monitoring and strategic litigation, with real follow-up on the implementation of judgments, is essential. Defenders and organisations facing smear campaigns, criminalisation, and funding cuts require flexible, multi-year support and a rapid response to threats.

The response also must counter “protection” narratives with rights-based protection: survivor-centred services, evidence-based education, and policies that reduce violence without scapegoating. Gender must remain central in peace and security, climate, and digital agendas, backed by budgets and political leadership rather than mere statements. Broad coalitions are essential, because anti-gender mobilisation is networked, funded, and strategic.

7. The Consolidation of Power Through the Closure of Civic Space ▾

The cumulative effect of restrictions on civic space is now creating a new reality. Funding restrictions, “foreign agent” laws, securitisation, surveillance, protest bans, digital shutdowns, smear campaigns, persecution and violence directed at civil society actors are no longer isolated tools. Together, they sustain a model of governance based on power consolidation, in which independent civic engagement is viewed as a threat to be contained or eliminated. This approach is central to the illiberal, autocratic playbook promoted by China and Russia and replicated across regions. Civic space is being deliberately closed, with fear being used as a tool.

To reverse this trajectory, civic space must be treated as core democratic infrastructure, not a policy preference. International actors should recognise patterns for what they are: systemic power consolidation, not technical regulation. Early and collective responses are crucial before closure becomes total. Benchmarks for civic space should be incorporated into foreign policy, security cooperation, trade partnerships and development agreements, with clear consequences for restrictions on freedom of association and protest rights, and for the persecution or attack on civil society actors.

Donors and institutions committed to democracy and human rights should stabilise and reconfigure their support for independent civil society. This should include flexible, multi-year core funding, rapid response and legal defence support, emergency relocation, and protection funding as a standard, not an exception. In parallel, civil society needs to strengthen its local presence and forge alliances to counter delegitimisation and demonstrate its relevance. Protection and solidarity networks are part of this work. The message must be consistent: independent civil society does not threaten stability; it is a prerequisite for accountability, participation and resilient societies.

8. The Delegitimisation of Human Rights Defenders, Including Those in Exile ▾

People on the frontlines of rights struggles, representing their communities and organising resistance, are increasingly subjected to delegitimization, as well as arrests and surveillance. These human rights defenders (HRDs) are portrayed as foreign agents, extremists, or self-interested elites, which makes repression easier to justify and harder to contest. For defenders in exile, stigma is paired with transnational repression, harassment of family members, cyberattacks, and the misuse of legal cooperation tools. This weakens solidarity, undermines access to protection, and erodes the early warning role that defenders play.

To counter this trend, states and institutions must treat human rights defenders as legitimate public interest actors and consistently affirm this status at home and abroad, even when defenders are unpopular or politically inconvenient. Protection frameworks must also adapt to transnational repression, responding more strongly to cross-border harassment, spyware, strategic lawsuits, and the misuse of extradition or policing tools. Exile should not add to the vulnerability of human rights defenders.

Funding should support not only emergency response, but also invest in sustainability and legitimacy of HRDs, their communications, community connection, and organisational continuity. Multilateral and regional mechanisms should treat delegitimization campaigns as early warning indicators of wider democratic erosion. Civil society also needs to form broader alliances that ground human rights work in shared social struggles.

9. The Erosion of the Right to a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment ▾

Although environmental rights are recognised in law, they are often sidelined in practice when they clash with economic priorities, energy politics, or short-term stability claims. Environmental defenders are increasingly being criminalised, facing strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPP), surveillance and administrative harassment — even in democratic states. Protest is reframed as disorder and civil disobedience as extremism, creating a chilling effect, rather than a vital voice in building public support for climate change mitigation. This delays solutions, deepens social conflict and harms communities already bearing the brunt of environmental damage.

To counter this trend, the right to a healthy environment must be integrated into domestic law, policy and enforcement, including meaningful access to justice and remedies. Governments should stop criminalising peaceful environmental activism and adopt strong protections to prevent litigation from being used as a weapon to stifle participation. Environmental defenders should be explicitly covered by environmental and human rights defender protection mechanisms, including emergency support and safeguards against transnational repression.

Environmental policy must also be founded on participation and social justice, because just transitions fail when communities are excluded. Regional and international bodies should treat attacks on environmental defenders as an early warning signal of a broader regression of rights and act quickly. Protecting environmental defenders is not a niche cause; it is an integral part of safeguarding democratic space and a liveable future.

10. Information Integrity Under Pressure: AI, Disinformation, Propaganda, and Movement Gaps ▾

Information spaces are increasingly treated as battlefields, being shaped by disinformation, propaganda, and AI-driven manipulation. Facts and evidence are undermined through repetition and doubt rather than by credible counterevidence. This has an impact on elections, war reporting and accountability for violations, because when facts are blurred, it becomes more difficult to establish responsibility. Human rights movements often lack the infrastructure and reach to compete in such polarised information environments.

To counter this trend, we must defend the conditions in which facts can be established, tested, and used to hold those in power to account. Information integrity is a human rights issue linked to participation, access to justice, and freedom of expression. Rather than taking shortcuts that create new tools for abuse, responses should strengthen transparency and accountability for coordinated manipulation, as well as safeguards against AI-enabled surveillance and profiling.

Civil society requires sustained investment in communications capacity, verification workflows and rapid response anchored in evidence. Independent media outlets, fact-checkers and local trusted intermediaries require protection and financial sustainability. Partnerships with educators, technologists, and community communicators could also help build shared reference points and ensure that facts are not drowned out by noise.

Human Rights Compass offers this as a practical tool. It is designed to support well-intended governments, policy-makers, institutions, and civil society in reading the landscape clearly, defending what is under attack, and acting with more consistency and political courage in a fractured order.

Human Rights Compass Policy Brief of 19 February 2026, resulting from a convening of over 30 leading international human rights defenders and experts, held on 25 November 2025.

GENDER BACKLASHRecommendations: Advancing Global Gender Equality

DEFENDING DEFENDERSRecommendations to Strengthen and Support Human Rights Defenders Amid Global Realignment

We are living through a period of profound “global realignment”. The multilateral human rights system — once grounded in universal norms and collective protection — is fracturing under geopolitical pressure. In this context, human rights defenders (HRDs) and the civic ecosystems that sustain them are at the forefront of democratic resilience.

FRACTURED ORDERRecommendations to AdvanceHuman Rights Multilateralism

Human Rights Compass Policy Brief of 12 June 2025, resulting from a convening of over 30 leading international human rights organisations and experts, which was held on 13 May 2025.

The integrity of the international human rights system is under threat as geopolitical realignment accelerates the dismantling of multilateral norms. The collapse of US leadership under the second Trump administration, coupled with consolidation of authoritarianism in Russia, China and their allies, has enabled the deliberate degradation of intergovernmental institutions designed to uphold universal rights.

SAVING LIVES,UPHOLDING RIGHTS

Recommendations to Bridge Humanitarian Aid and Human Rights Amid Global Realignment

Recommendations to Bridge Humanitarian Aid and Human Rights Amid Global Realignment

The 2025 Global Humanitarian Overview estimated that over 300 million people in 73 countries were in need of humanitarian assistance as of late February 2025 – enduring severe suffering due to protracted conflicts, economic instability, climate emergencies and displacement. Global needs were expected to rise and the funding to decline. At about the same time, the shockwaves of the Trump administration’s decision to abruptly freeze and cancel several types of government funding reverberated through the international humanitarian community.

GLOBAL REALIGNMENT

Recommendations on how to avoid an adverse impact on human rights

The beginning of Donald Trump’s second presidency in the United States is creating, and coinciding with, attacks on the global human rights landscape. Since 20 January 2025, the world has witnessed the erosion of the rule of law in the US and the unravelling of a system that has shaped the international order for the past 80 years — the multilateral rules-based order based on the Franklin Roosevelt blueprint of collective security, economic multilateralism and political self-determination.

In barely two months, the new administration has terminated critical humanitarian aid; withdrawn from international organisations, fora and agreements, notably the climate, health and human rights platforms; curtailed long-standing support for human rights and democratisation efforts abroad; and challenged economic, political and security alliances. It rejected the principles of diversity, equality and inclusion, empowered anti-LGBTQ and racist rhetoric, and accelerated the backlash against gender equality and women’s rights.

The void left by the Trump administration’s approach to democracy, multilateralism, and human rights is immense and requires an urgent response from political leaders and civil society.

New leadership and new frameworks are needed to protect human rights and rule of law in this context. New approaches and new coalitions - on the state and civil society level — should fill the void and human rights must be at the heart of any new order that emerges.

Human Rights Compass is endorsed by:

Gunnar Ekeløve-Slydal

Elisabeth Pramendorfer

Mamikon Hovsepyan